10 Years in Manufacturing: Skills, Insights & Real-World Experience

I worked in manufacturing automation for multiple employers before becoming my own boss. This had huge benefits in developing my knowledge and hands-on skills.

My mechanical engineering degree opened up a vast number of possibilities, especially in the manufacturing-heavy Southeastern US. During my tour of the Upstate (South Carolina) I worked for two automotive suppliers, a smart meter company, a manufacturer of fire sprinklers, and briefly for a textile equipment company.1

My skillset became not so much how to make an individual product, but the ability to work with and develop manufacturing automation in a variety of settings. So what did I learn during this decade-or so period of my life? Read on to find out!

Build hands-on confidence in the machine shop

If mechanical engineering is the core of engineering disciplines2, you could argue that automotive the heart of mechanical engineering. While I had less interest in automobiles than many of my colleagues, I nonetheless interned3 at a plant that made needle bearings, which were sold to automotive customers and installed elsewhere.

What made this gig really excellent (besides the very good pay for a college student) is that they allowed me to use the machine shop in a relatively unrestricted manner. This was done under the general supervision of a handful of machinists, and ultimately under an engineering manager who largely left me to my own devices. During this year-long alternating term, I went from someone with very little hands-on experience, to someone comfortable “turning a wrench,” and using a variety of shop tools (e.g. milling machine, MIG welder).

I was even able to finish several minor machine builds. This gave me experience in the “real world” of engineering, and familiarity with electronics, pneumatics, PLC programming, and more. While much different than the more traditional math/physics/books portion of my engineering education, this gave me a set of skills, and more importantly the confidence, to step out on a limb and make things that follows me to this day.

Just because it sounds awesome doesn’t mean it is

Fast-forward to graduation from college, and I found myself looking for a more permanent job. I really envisioned myself as a design engineer, working on robots, tanks, radars, or whatever other thing was of interest. The job market at the time was lukewarm, but I was hired at a company that made custom cooling components for performance vehicles, including race cars.

This sounded awesome, per how the end product was used. The reality, however, is that my job was supervising a number of braze ovens that welded radiators together. For me, the relationship between this an anything as cool as race cars was tenuous at best. Making things worse, they seemed to be having financial trouble.

That job ended before I had the opportunity to become useful. Learning to work in any industry takes time. A few months later I was hired as an engineer at the same company where I interned.

Manufacturing: an amazing engineering skills classroom

First of all, manufacturing is stressful. I didn’t always like it, and there was a lot of adjusting and fixing machines over and over until the time when I could (hopefully) implement a more permanent fix. When a machine isn’t working, the company is literally loosing money, and as an engineer it’s up to you to fix it, with no excuses. That was often difficult, and honestly I could have handled the stress better at times.4

However, with all that stress came a massive amount or learning. Manufacturing plants tend to employ mechanical engineers as their main technical resource, often with industrial engineers, electrical engineers, and IT staff providing secondary support in their respective realms.

The long and short of it is that I was able to (i.e. had to) supplement my traditional mechanical engineering knowledge and aptitude with electrical engineering and (PLC) programming skills learned on the job. I even set up a number of vision systems, and a SCARA robot cell for packing duties in one instance.5

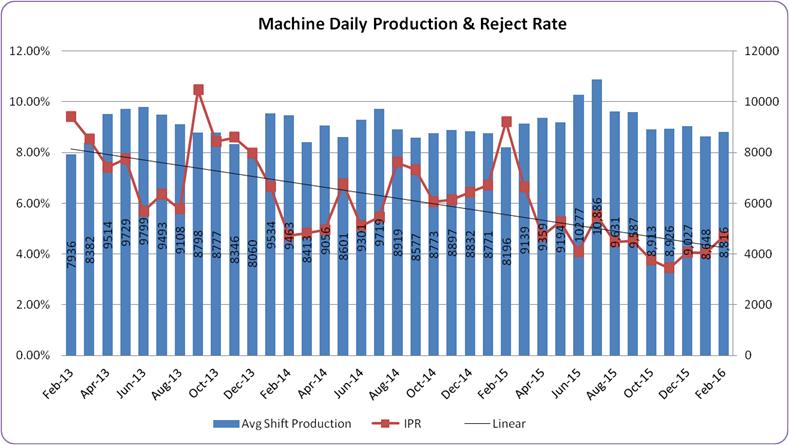

Make Improvements, Track Improvements

At the needle bearing factory, and at other posts through the years, I designed a number of manufacturing cells from the ground up, and revised others to the point that they were largely new machines. Such builds typically took a few months, allowing me to see the progress from idea, to CAD model, to physical thing, to functional device.

That part of the job was incredibly satisfying and certainly the most fun thing that I did. If I didn’t work for myself as a technical author and builder of various contraptions, a role as an integrator, devoted solely to process development for manufacturing, would probably be my ideal job.

One great thing about being able to improve machinery and processes is that you get bothered with petty problems less and less. The other proverbial edge of this improvement sword is that you can tend to work yourself out of a job. The company may eventually start to see your salary as a drain,6 so make sure to keep track of how much money you’ve actually saved them with these improvements.

While this may or may not save your job–and at that point it might be time for a new challenge anyway–it can certainly help when you need to negotiate compensation or look for a new position!

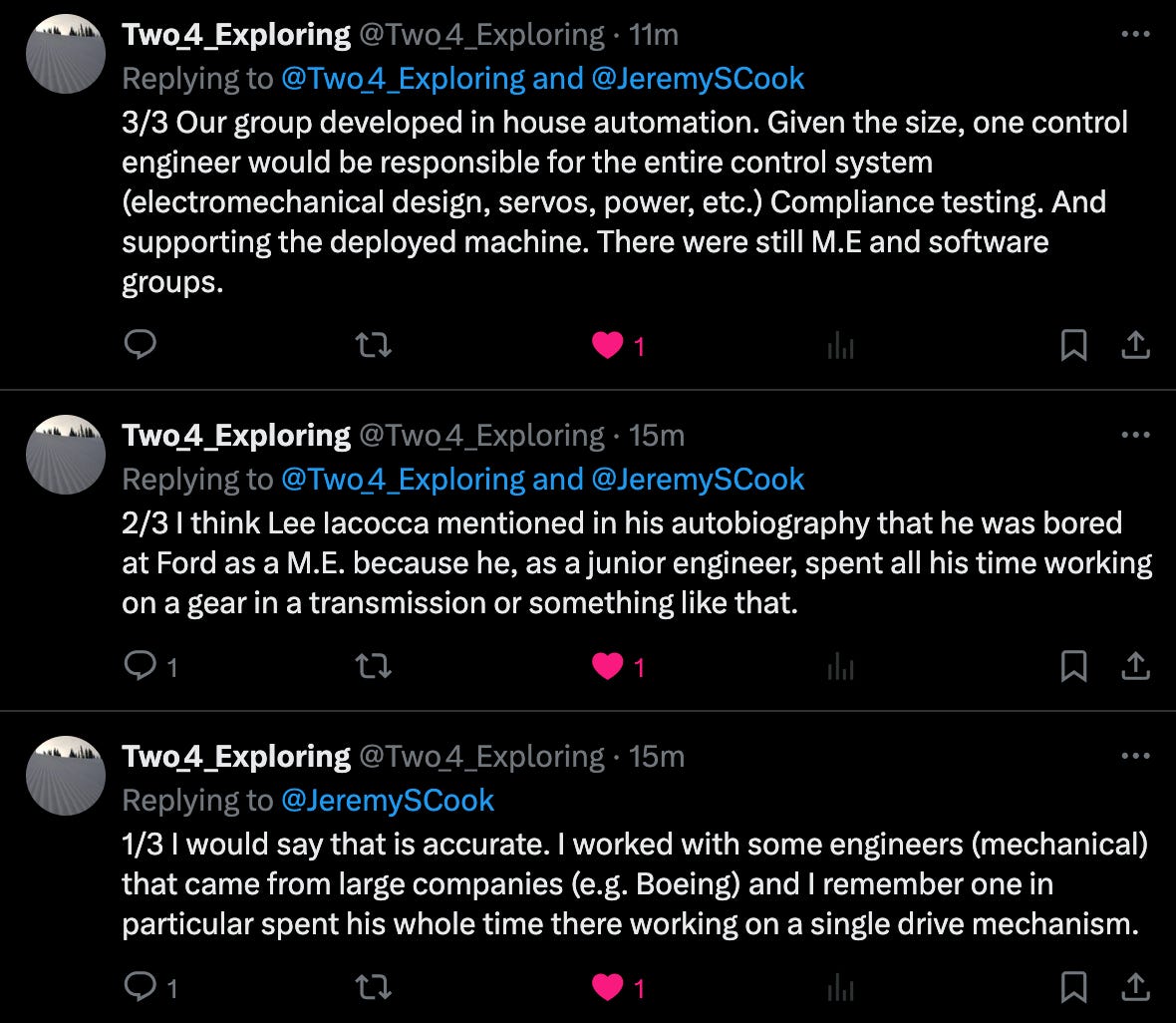

Small Part of Big Project - Or HUGE Part of a Small Project?

If you’re working on a really impressive project, you’re likely working on a small bit of a large “thing.” For example, while thousands of people might work on a new jet, most engineers were likely optimizing a small part of the overall picture, e.g. the seat, part of a seat even.

The satisfaction of “I built X,” (along with 2000 others) would seem to be less than the engineer that says “I built Y” MYSELF, even if it’s not, say, the space shuttle. Such one-man projects can be your own little electromechanical fiefdom, often given you a lot more freedom to solve a given problem.

OTOH, I might make an exception to this rule for Space X vertical rocket landings. They are truly surreal to watch. Cape Canaveral is only a few hours away from where I live, so perhaps one day…

Of course, you don’t–and can’t–know everything… even if some people think they do. The good news is that you don’t (always) have to know the answer. Even a small team of smart people with their own diverse skills can help a project go smoothly.

I have cherished times in my career where I’ve been able to handle the mechanical (and generally the electrical) design portion of a project, then pass it off to to an EE/Test Engineer for programming duties. Often this person could be a great resource if I was laying out the electronics and wanted a second opinion.

If you have design reviews or other impromptu meetings among your team and/or other personnel, they can be a great opportunity for learning. Depending on the environment, such design reviews can be a lot of fun, potentially devolving into the sort of ribbing that you thought was long gone after middle school.7

Have a Plan When Working for Someone Else

While it sounds great to be your own boss, consider that you can learn a massive amount by working for a company. You get access to (hopefully) knowledgeable people, as well as equipment and technology that you wouldn’t be able to afford otherwise. Best of all you get paid for the endeavor.

My stint in manufacturing was hugely beneficial, both in the fact that I have something to write about, and for the satisfaction in being able to make things. I can’t imagine being happy not being able to express myself with physical things that I’ve designed and produced. See my Tindie store for a few examples.

If I were to look back and zoom out on my career so far, I wish I’d really considered were I wanted to go with it. You can’t expect your manager or anyone else to make your plan. You have to take the reigns, or be prepared to simply accept where life takes you.

Which might be fine, or it might not. I’m pretty happy all things considered. Given a few changes along the road, things could have been much different, both for better and worse.

When you’re first starting out you don’t know what you really want to do with your life and what specialty will really suit you. If have any questions, feel free to get in contact via the comments or shoot me an email at hi@jeremyscook.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Any Amazon links are affiliate

Addendum/Footnotes:

That job was truly horrible. After enduring quite a bit of chewing out from the owner of the company for rather insignificant "transgressions” over my short employment there, he eventually fired me, saying that they needed someone clever in that position, i.e. not me. It seemed like he wanted me to get angry and start yelling back at him for his validation. Instead I said, “That would be really hurtful if you were someone I respected.” If I’m being honest, the comment was a bit hurtful.

He also questioned my grasp of the English language, asking if my wife (then an English teacher) did my resume and/or cover letter for me. Sure, I make the odd mistake or two in writing and engineering, but I think I’ve proven my mettle since then in both cases. Have I always been the best employee everywhere I’ve worked? Admittedly, probably not. I’ve received criticism at times that I certainly deserved.

Looking back, that was simply a bad place to work. However, it’s hard to know if that’s the case, or to have the proper perspective in the moment. I should have simply resigned when I saw that job jumping the shark (or jumping the worm, if you’re a Dune fan), but it seemed to make financial sense to suck it up at the time.

I’m not saying ME is better or worse than other disciplines, but I think it probably covers more industries than any other field. Also, many concepts that are core to ME need to be known as general knowledge in other fields (if to a lesser extent), e.g. statics.

Technically I co-oped. Like an internship, but working for a year on alternating semesters. In theory you could do this (plus summer sessions) and still graduate in four years, but that was uncommon. I was at Clemson for 5 years as an undergrad, which was fine with me, especially since the position payed well for a college student.

This extra money allowed me to buy a car, which was part of my motivation for taking the job in the first place.

Josh, a friend of mine from college, who also worked at the bearing plant as an engineer, once noted that it was helpful to mentally zoom out from your current state, and remember that this will be over next week, next month, next year, etc. It’s a helpful exercise no matter what challenge you’re going through.

Here’s my robot cell, packing bearings and lifting the trays with its vacuum grippers:

This blurb about “absence blindness” from The Personal MBA book seems quite relevant.

There’s a fine line when it comes to design review joking around and insults. In one case a project for which I was handling the mechanical portion got branded as the OFI machine, the long form of which was… inappropriate. This somehow got passed along to upper management (beyond my immediate boss, who was either the originator of this name or fully onboard). The result was much unhappiness passed down from above, and one or more disciplinary writeups.

Note that this moniker wasn’t insulting to my design, and since I was fairly new to the company at the time I tried to stay out of this controversy as much as possible. That being said, I very much enjoyed working for the engineer who was my immediate boss at the time, and with that engineering group. What that says about me is an open question.

At that same company, there was a (later) incident where a reference was abbreviated as “Gold STD” on a drawing. I and another engineer started referring to it as the “Gold S-T-D Machine.” My (different) boss didn’t think that was very funny. Nor did he think the moniker for my “AVMS Machine,” which stood for “Advanced Vertical Mounting System” was appropriate. He (admittedly, correctly) saw this name as meaningless. An early draft of the machine looked of like a tree with electrical meters hanging off of it, so the name sort of made sense in my mind.

In fairness, “different boss” wasn’t a bad guy either, and we got along well. While some have been better than others, I’ve had very few immediate bosses that I didn’t like (see note 1).